The term coronary vascular disease refers to the development of plaque in the walls of any artery in the human body. If plaque formation occurs in the arteries to the heart, it is referred to as coronary artery disease. If it occurs in the arteries to the brain or other arteries, particularly the legs, it is called carotid vascular disease and peripheral artery, respectively.

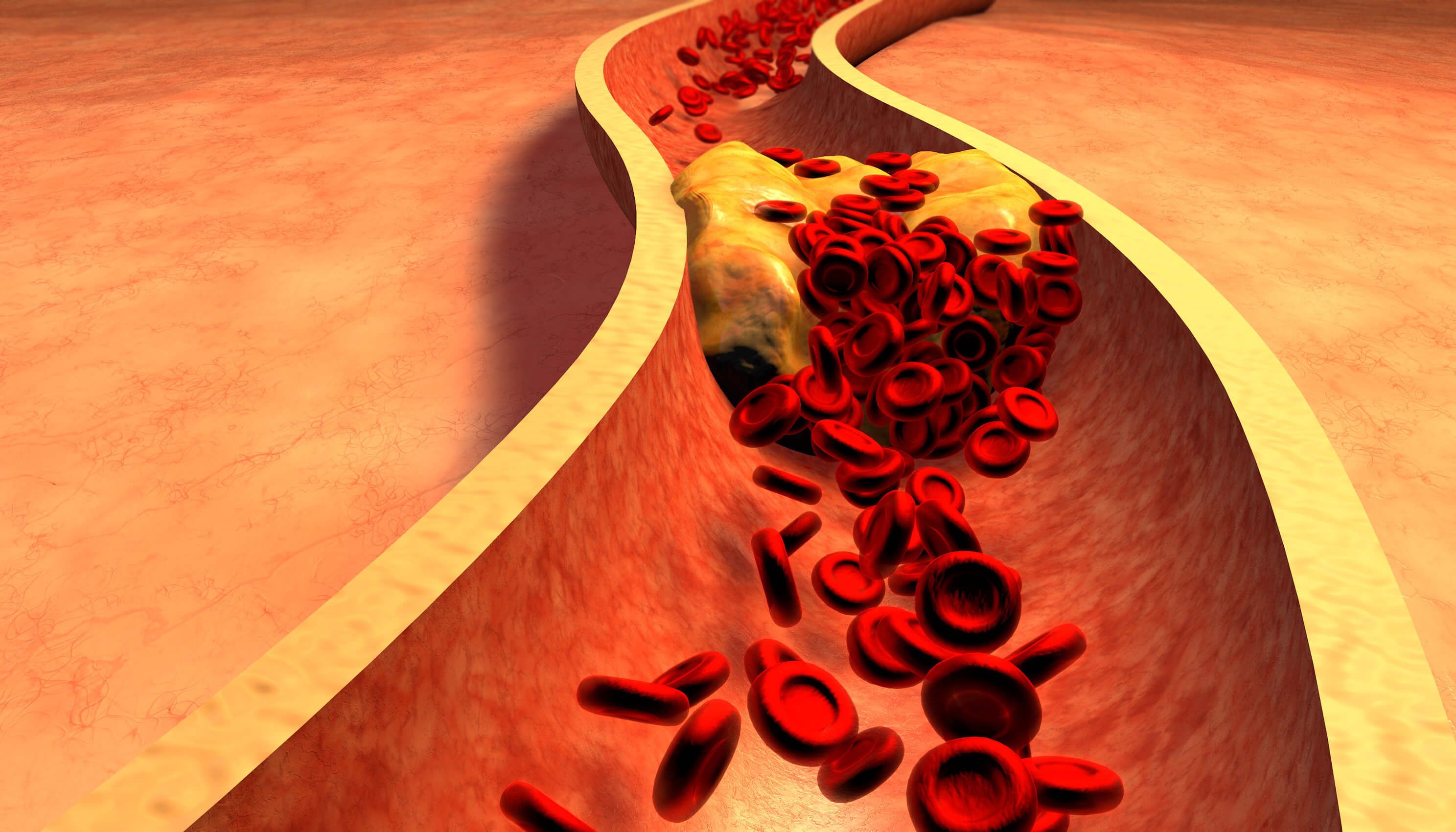

The development of plaque, sometimes referred to as vascular “crud” or “rust,” results from the exposure of the inside of the arteries where it is exposed to cholesterol in the bloodstream. This is referred to as atherosclerosis. There are two main types of plaque: soft plaque, similar in consistency to the layer of fat one finds on soups that have been refrigerated, and calcified plaque with a chalky composition. When the plaque accumulates in the artery enough to cause obstruction and restricts blood flow, it can cause symptoms in the coronary arteries, such as chest pain with effort, or when it occurs in the peripheral arteries can cause pain in the calves with activity. The most feared complication of atherosclerosis occurs when the blockage, or stenosis, completely occludes an artery leading to a heart attack, sudden death, stroke, or severe leg pain, at times treated with amputation. Usually, the cause of the occlusion is the formation of a blood clot or thrombus composed of platelets and clotting proteins on top of a cholesterol plaque that has ruptured or fissured.

There are several contributing factors to the development of plaque or atherosclerosis and its complications, including death, heart attack, stroke, and potential amputation. These risk factors include elevated cholesterol, high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, tobacco use, and of course, genetics or a family history of heart attack or stroke. Cholesterol plays the most important role, what we call attributable risk, so it is a focus of our efforts to prevent the complications of atherosclerosis, along with smoking cessation and treating blood pressure and diabetes. When we talk about cholesterol, this discussion needs to include LDL, which most of us are familiar with as the “bad cholesterol,” but also triglycerides, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, and the worst of them all, lipoprotein a, also referred to as LPa or the “horrible” cholesterol. We also know that inflammation plays an important role in the development of atherosclerosis, which is also a target of clinical trials to reduce it.

Lowering cholesterol, particularly LDL or the” bad cholesterol,” decreases the risk of developing atherosclerosis and its complications. A good rule of thumb is that for every 2% one reduces LDL, the risk of heart attack and stroke comes down 1%. Some people who are on cholesterol treatments or lipid-lowering therapy raise the concern that their cholesterol can be too low. This does not seem to be the case in adults, as we know that newborns do perfectly fine with very low levels of cholesterol. Yes, we do need some cholesterol for the development of our nerves and brain and for the body to make or synthesize sex hormones such as testosterone and estrogen, and cortisone-like hormones.

Cholesterol production occurs in the liver mostly under genetic control, as only about 15% of our cholesterol comes from our diet. The liver is also the organ responsible for breaking down cholesterol. So, it makes sense that most lipid-lowering treatments target the liver to exert their cholesterol-lowering effects. The most commonly applied cholesterol-reducing treatments are statins. Statins at maximal doses lower cholesterol by about 50%. Other medications that we use to lower the LDL cholesterol include Nexletol or drugs that block the effect of a circulating protein called PCSK9 that inhibits the liver’s ability to break down cholesterol, including Repatha, Praluent, and Leqvio, and medication that blocks the absorption of cholesterol from the intestine called ezetimibe. We do have a medication that lowers triglycerides by about 25% called Vascepa.

We have information from recent clinical trials that show that if one can lower the LDL cholesterol to less than 50 mg/dl, one can actually see the resorption of soft plaque in arteries. Once patients develop more advanced blockages, we use medications that keep blood clots from forming on plaques. The most common medication to prevent blood clots or thrombosis on the plaque is aspirin, but other medications, such as Plavix or Brilinta, are sometimes used. When patients have symptoms that cannot be controlled with medication, they can be treated with stent procedures to open the arteries or bypass surgery to use a vein or another artery to create a bypass around the blockage.

Even with these commercially available medications, the residual risk of developing complications is only reduced by 30-40%, so 60-70% of events still occur. This has led the National Heart Institute to focus on new and potentially more effective and safer treatments that lead to reductions of lipoprotein a, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol, as well as reducing inflammation in our clinical trials and further mitigate and reduce the risk of developing complications of atherosclerotic coronary vascular disease, the number one killer of Americans.